Govt brews national cloud for science

- 07 January, 2010 11:37

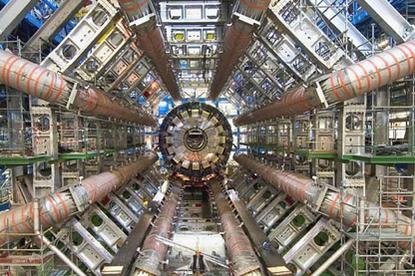

Australia's scientific community is planning to tighten links between Australia’s cloud research networks and the mammoth grids spread across the Northern Hemisphere, like those used in the Large Hadron Collider.

Australian scientists will have access to a multi-million dollar national cloud network and $50 million towards a petabyte supercomputer and data centre within three to five years under slated improvements to the nation's grid networks.

The upgrades will make it easier for scientists working in fields such as cancer research, space exploration and mechanical engineering to access the nation-wide computer networks without requiring complex IT skills, or in most cases, without paying a cent.

Grid networks provide unparalleled compute capacity critical to processing the huge data streams generated by cutting-edge scientific research. Such research would often be stonewalled without access to each state's High-performance Computing Facilities and the thousands of smaller clusters spread across the country. Disparate groups of all sizes can pool compute resources into a grid, and provision equal access to data and processing with minimal IT know-how.

Organisers are also planning to tighten links between Australia’s cloud research networks and the mammoth grids spread across the Northern Hemisphere. Europe's Enabling Grids for E-sciencE (EGEE), the largest in the world, gained international attention during lead-up to the 2009 failed launch of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Switzerland and its subsequent refiring at half capacity last November, with media reports claiming the supporting grid networks including that operated by the European Organization for Nuclear Research, CERN, would change or even replace the Internet.

While other experts are less prophetic, these grids are at the forefront of network computing; the CERN network includes some 20,000 mostly Linux-based servers spread across Europe and the US, while the EGEE presently supports more than 10,000 researchers and processes about 150,000 compute jobs a day that amount to hundreds of terabytes of data.

Most recently, the networks have helped Australian researchers discover a way to 'smart bomb' cancer using radioactive drugs without damaging adjacent cells, and save time and money in the transportation of data for CSIRO and NASA radio astronomers, while Holden uses the network to help design and test new safety features and aerodynamics in its cars.

The Atlas of Living Australia (ALA) will also use the grids to create analysis tools and collate data on the country's the 250 million flora, fauna and microbes, a task recently propped up with an additional $30 million in funds to 2011 from its initial $8.2 million.

Upgrades are well underway for Australia's foremost research datacentre, the National Facility, lead by the National Computational Infrastructure (NCI) group and situated in Canberra. Director Lindsay Botten said the processing capacity of its Sun Constellation supercomputer rose from 25 to 140 teraflops last year (2009), and will reach 200 teraflops by year’s end (2010) and eventually exceed a petaflop by 2012.

"Everything is heading towards data-intensive science, and effective network access speeds will go through the roof," Botten said.

"The federal budget funds - $20 million for the data centre and $30 million for the petascale computer - were allocated for the next two years to provide compute resources to specific research areas like climate change, which itself received substantial money."

Climate change research will receive the lion's share of the facility's resources along with the existing network of seven supernodes that each contain about 10 petabytes of data.

The lands of the long white cloud

Australia and New Zealand researchers will within five years jointly operate under a trans-Tasman cloud network that promises to be simpler, and more standardised and scalable than the current grid. It will be spearheaded by grid operator the Australian Research Collaboration Service (ARCS), which despite discordant opinion on what differentiates a cloud from a grid, says the upgrade is a natural progression that will benefit from developments like the government's $43 billion National Broadband Network (NBN).

Page Break

The local ACRS grid connects eight High Performance Computing Facilities in each state, including the CSIRO, with a growing list of university cluster networks. Systems services manager Jim McGovern said a cloud model will provide users with better ease of use and more flexibility.

"For example, researchers will be able to package programs in a virtual machine and send them off to whatever facility is best suited to process [the data], but before that happens, we will continue unifying the resources so the many scientists who aren't in IT can easily use the network," McGovern said. "The cloud will be able to better utilise availability and schedule jobs to free processors".

University researchers will eventually be able to authorise with the network using their internal credentials through the Australian Access Federation, which also serves as an education medium for users.

The ARCS is planning to expand its international grid links that connect Australian and New Zealand researchers to the big European and US networks. McGovern says local processing capacity is sufficient but there is room for improvement in international research collaboration.

Expert opinion, however, is divided on the benefits of cloud over grid architecture. The European Infrastructure Reflection Group says even the best cloud offerings are not yet sophisticated enough to support complex grid-like use, and that research community "would be best served" with a mix of grid and cloud-based services. It further notes that grids are better equipped to handle large bursts of processing, while clouds are more suited to longer-running compute jobs.

McGovern said the consumer sector will benefit from the experience of the grid operators in dealing with record network traffic levels, and the pressing need for interoperability developed without commercial pressures.

Mapping out funds

While public and private sector science research funding has been buoyed with a 25 per cent increase, or $3.1 billion over the next four years, the government will need to doll out more cash prior to 2012 to support the grid expansion, according to Botten.

He says the $50 million allocation to the supercomputer data centre supplied under the National Collaborative Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS) will not pay for maintenance or staff wages. Researchers rely on a whopping $7.5 million a year from grid partners, compared to $1.6 million from the government which is set to close with NCRIS by 2011.

"A decision in NCRIS' extension has only been partly taken by government. There is a lot of co-investment that has to be found to keep a $30 million supercomputer alive; we're talking about multi-million dollar power bills each year," Botten said. "There is a need to fund people... the universities are generally cash-strapped, so generating levels of co-investment can be difficult."

New supercomputer data centres like the National Facility will be targeted to support specific fields, rather than a scatter-gun approach where all scientific fields have equal stake in resources. Large organisations and universities have joined the Bureau of Meterology to fund the climate change component, but Botten said the model will need to be shifted so research is not sidelined.

"There will have to be rearrangements down-the-track so that those scientific organisations that do not reside in the priority areas will have access to the compute resources. It will wash itself out through co-investment - eventually everyone will have to chip in to help maintain the machines and they will in turn own a stake of the resources for whatever scientific fields are important to them."