Too... much... data

Cloud was always, in retrospect, going to be a natural fit for JPL. The organisation has around 5000 people and, Shams says, "we are busier than we ever have been before". "We've got missions that are going all over the Solar System, we have landed missions on Mars recently, and we have been to every planet in the Solar System. And recently we've started having much more focus on earth science. And the problem is that with earth science we have the opportunity to get a lot more data."

"So we're really busy, we've got all these missions going all over the Solar System and beyond, and our data centres are getting filled to capacity and our data needs are growing faster than ever," Shams explains.

"In come the earth science missions — and over the next couple of years we're going to be getting two terabytes of data per day from some of these missions. And this is a scale that is orders of magnitude bigger than what we've ever seen before.

"So we're running out of space, we're running out of capacity. We want to be able to use the physical space that we have at our laboratory for people and for science rather than running infrastructure. We're also noticing that cloud vendors are starting to offer these capabilities and infrastructure at a much lower cost. And add to that the elasticity that is available to us in the cloud diminishes our cost even more."

This combination of on-premise infrastructure reaching its limits, an onslaught of data and the limited timeline of some of JPL's missions — some only last for six months — made cloud an inviting option for the organisation. When a mission is underway, JPL "really process the data as much as we can for those six months [for example], and then that infrastructure is going to go to waste after that. So with cloud computing, we're able to say, 'Okay well we're just going to pay for it while we use it and turn it off when we're done. '"

Using cloud for computationally intensive processing mitigates the risks associated with capital investment, Shams adds. Before employing cloud computing, the IT infrastructure for a mission would be purchased a year or more in advance: It would be tested and then put in change control configuration and not used until the actual mission took place.

"Now there's a risk here that if the launch is unsuccessful we have made all this investment and this infrastructure's not going to be used," Shams says.

"The other risk is that we have paid too much for this infrastructure because we bought it a year in advance. So now move forward four years — cloud computing. Let's say there's a hundred machines that we needed. We have the opportunity to bring up the hundred machines [in the cloud], test everything worked, shut them down, don't pay for anything and if the mission is successful — which almost every time it is — we just launch those machines, just as if we left them, and start paying for them immediately."

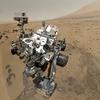

Getting to the point where Shams could ramp up instances in AWS for the data pipeline from Curiosity to Earth was not straightforward, however.

There are a lot of government regulations NASA has to abide by. The good news, Shams says, that all the downlink data the space agency collects can be released into the public domain, which was an important factor that let JPL experiment with cloud computing while navigating these regulations.

NASA has worked closely with cloud vendors to find ways of using cloud that don't fall afoul of the law; for example Amazon established its GovCloud in the Oregon Region, which offers the same security as AWS public cloud but is compliant with ITAR — the International Traffic in Arms Regulations — which governs the movement of sensitive data: Data won't be shifted offshore and the facilities are staffed only by "US persons" (a category that includes US citizens and certain permanent US residents, among others).

And while it may have only taken a bungled procurement order and a conversation to set things in motion — making it happen took a lot longer. For example, the first contract that JPL signed with AWS took eight months.

"At that time, cloud vendors weren't ready for the enterprise," Shams says. "They were still built for the start-up with a credit card, or Joe Smith with a credit card. Having to deal with the enterprise was something they were learning first hand."

Dealing with a government agency involves an even steeper learning curve, due to the regulations that must be abided by when dealing with an organisation like NASA. But that eight months wasn't wasted: not only was the contract signed in the end, but Soderstrom conducted a retrospective to identify blockages in the process that could be removed to ensure smoother sailing as NASA continued to embrace cloud.

"The reason why it took us eight months is because there was a long communication chain," Shams says.

The convoluted communications chain involved Shams communicating with NASA's procurement team, which would have to talk to NASA's legal team as well as Amazon's sales team. On top of that JPL's security team was also an obvious stakeholder.

On the Amazon side, they also had their security team and compliance and legal teams. The upshot was a communication pipeline ripe with potential for blockages and channelled through Khawaja and the procurement team.